In the book of the prophet Isaiah, God teaches mankind, “my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways… For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, my thoughts higher than your thoughts.” (Isa 55:8-9 NABRE). The words of God in this passage, spoken through the Prophet, remind us that no matter how hard we try to come to a full knowledge and understanding of the ways of God in this life, we will still fall short. Modern skeptics argue against faith and the truth of Scripture with intelligent, well-researched, and well-structured arguments based on seeming inconsistencies found within the supposedly-inerrant Scriptures. The “Method B” approach of the modern, historical-critical skeptic zooms into snippets of Scripture and focuses on the origins, historical settings, and truths surrounding the text to understand it from a scientific viewpoint. Because of such a read, and forgetting that “[God’s] thoughts are higher than [our] thoughts,” a skeptic using this approach is unable to explain seeming contradictions scattered through the entire Canon of Scripture, or singular events or stories that stand in contrast to the full, revealed truth of God’s nature and essence. Particularly in the Old Testament, there are many different types of contradictions noted by modern scholars: the nature of God, the nature of good and evil, and the nature of the afterlife.

One of the major contradictions noted in the Old Testament by modern scholars and skeptics is the presence of so much evil directly or indirectly caused by, or seemingly ordered or permitted by, a God who is otherwise presented as all-loving, all-knowing, and fully-benevolent. This paper will outline some of the modern (Method B) challenges to the inerrancy of Scripture, specifically stemming from this “problem of evil,” outline some of the traditional arguments against this concern from the Church’s history and tradition (Method A), and explore some of the ways that these arguments can be synthesized using a new method that can help better serve a modern audience. It will also explore some of the principles one must understand and address to prepare an appropriate response for the modern Method B skeptic.

To overcome these critical challenges, today’s Christian apologist cannot expect to rely solely upon ancient arguments of faith, predominantly written/provided by the Doctors of the Church and passed along in the Church’s Tradition. These arguments, referred to as Method A exegesis, are useful in explaining or building upon an understanding of elements of Scripture for a person who already has the gift of faith. However, for a skeptic, they typically lead only to more questions or objections and do not carry much credibility in modern argument devoid of faith. Pope Benedict XVI, when he was still Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, proposed a new method of exegesis, Method C, which marries the strengths of both Method A (insights from the legacy and inherited tradition of the church) and Method B (a careful, historically-informed reading of the text). When proposing his Method C, Benedict layed out a vision in which a faithful scholar could incorporate Method B questions, interpretations, and approaches, insofar as they don’t conflict with the depth of knowledge and insight from the Church’s treasury of tradition (Method A), and bring the two together into a new approach, rather than relying solely upon one or the other. Similar to how Benedict saw the opportunity for the old and new forms of the liturgy to be “mutually enriching,”[note]Benedict XVI, Letter of His Holiness Benedict XVI to the Bishops on the Occasion of the Publication of the Apostolic Letter “Motu Proprio Data”, Summorum Pontificum, on the use of the Roman Liturgy Prior to the Reform of 1970 (7 July 2007), par. 9, Holy See, accessed October 2, 2017, https://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/letters/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_let_20070707_lettera-vescovi.html[/note] he also imagined an approach to Biblical scholarship by which tradition and modern exegesis could mutually enrich each other in his Method C.

As noted, one major objection raised by modern skeptics is the presence of so much evil in the creation of a good God. In God is Not Great, the New York Times bestseller by popular skeptic Christopher Hitchens, he “presents his readers with everything from ‘demented pronouncements’ in Scripture to the more serious ‘atrocities’ committed by God and the people of God.”[note]Matthew J. Ramage, Dark Passages of the Bible: Engaging Scripture with Benedict XVI & Thomas Aquinas (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2013), 179.[/note] In Benedict’s September 2006 address at Regensburg, he asserted that “violence is incompatible with the nature of God.”[note]Ibid, 180.[/note] One hundred Muslim leaders responded to his assertion, referring to God drowning Pharaoh and his armies in the waters of the Red Sea, and asking the question, “When God drowned Pharaoh, was He going against his own Nature?”[note]Ibid.[/note] It is a very valid question, posed by educated men in the modern world, of how a good God can permit or enact some of the evil events found in Scripture.

Some of the instances of evil in the Old Testament that Matthew J. Ramage explicitly calls out in Dark Passages of the Bible, Engaging Scripture with Benedict XVI & Thomas Aquinas, include God destroying everything but Noah’s family and the animals with them in the ark in Genesis 7, the killing of the first-born throughout the land of Egypt (the Passover) in Exodus 12, the destruction and conquest of Canaan in Deuteronomy 20, and the killing of every man, woman, and child in those conquests in Deuteronomy 2.[note]Ibid, 181.[/note] These certainly are difficult texts to explain. Before our discussion turns specifically to answering for some of these texts, it is important to explore two overarching concepts in Biblical exegesis: Scripture’s apparent development, and the existence of apparent contradictions in Scripture.

One of these areas that one must tackle first when dealing with modern criticism of the inerrancy of Scripture is the problem of Scripture’s apparent development, namely “that not all portions of Scripture explicitly teach the fullness of revealed truth Christians expect to find in the Bible.”[note]Ibid, 92.[/note] Put simply: Scripture developed over time, as man’s understanding of God and what God was revealing to man developed (the “divine pedagogy”). The idea that Scripture developed over time and may have competing or developing viewpoints on things like the nature of God seems to come into conflict with the idea that all of Scripture is inerrant. However, it is important to understand that the fullness of what Scripture teaches was developed over time, and wasn’t fully “baked” or understood by man in the early books of the Bible. While the fullness of revelation was expressed “when the fullness of time had come” (Gal 4:4), earlier generations, particularly through most of the history told throughout the Old Testament, were still learning about God through revelation as time progressed. In our present discussion, this is illustrated by the presence of things that God did, permitted, or “encouraged” that appear to be evil in the Old Testament, and that are in opposition to the all-good nature of God supposed by believers and presented elsewhere in Scripture. St. Thomas Aquinas provides the framework to tackle this problem of development, allowing us “to defend the inerrancy of early biblical texts which fail to explicitly display… an understanding of evil consonant with Christian doctrine.”[note]Ibid, 92-93.[/note] Aquinas suggests that the substance of the faith never changed – it was always present. Instead, what developed over time was man’s understanding of that substance of the faith, and the number of truths as God revealed it over time. He wrote,

“As regards the substance of the articles of faith, they have not received any increase as time went on: since whatever those who lived later had believed, was contained, albeit implicitly, in the faith of those Fathers who preceded them. But there was an increase in the number of articles believed explicitly, since to those who lived in later times some were known explicitly which were not known explicitly by those who lived before them.”[note]Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, II-II, q.1, a.7.[/note]

These “articles” of which Aquinas speaks are the subjects that the faithful know or believe. While they increased or were known about more explicitly over time, the substantive truth of God and faith did not change over time. Why would God reveal these subjects, even these truths about Himself, over time? One reasonable explanation is that it took time and discernment for man to come to understand, grasp, and assimilate these truths. Much of the Old Testament, in fact, is a story of the people of Israel learning something from God, accepting it for a time, then turning back away from God until they learned through trial and error that society, culture, and life were better when they were living in the ways that had been revealed to them. Aquinas says, “Man acquires a share of this learning, not indeed all at once, but little by little, according to the mode of his nature.”[note]Ibid, q2., a.3.[/note] Aquinas provides a helpful framework for combining the unity of Scripture stressed by Method A, while acknowledging and integrating the apparent development within Scripture often noted by Method B.

Another area that must be tackled when overcoming modern objections to Scripture’s inerrancy is that of apparent contradictions in Scripture. This correlates directly to some of the areas this paper explores – how an all-good God can cause or permit any of the evil that is apparent in the text of Scripture. To help tackle this area of contradictions, it is again helpful to turn to St. Thomas Aquinas and his insight into how Scripture came to be written. First, Aquinas applies a broad lens to the idea of “prophesy”, saying that every Biblical author is a “prophet” since they were revealed things by God[note]Ramage, Dark Passages, 115.[/note], then saying that prophesy is “something known by God and surpassing the faculty of man,”[note]Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, II-II, q.174, a.1.[/note] broadening the concept of “prophesy” to include much more than what is typically considered to be prophesy. Then, he introduces the idea that a prophet is moved to write in two steps, first “inspiration,” in which God opens his mind to be ready to receive some piece of knowledge, and then “revelation,” in which that knowledge is revealed to the prophet. A simple analogy would be considering inspiration as preparing the soil to plant a seed by digging and preparing a hole, and then revelation as planting the actual seed into the soil. Aquinas posits that in at least some cases, God inspires the prophet, inspiring and opening his mind, but then the prophet sets to writing before revelation has occurred. What is to be said of the divine authorship and inerrancy of Scripture, then? Aquinas would say that, in the way that an author can write something that still incorporates and formulates the ideas of others, God can be the author of Scripture, but still incorporate and permit the inclusion of the ideas of its human author, the prophet. These ideas might include indications of the cultural or historical place and moment in which they reside. In commentary on Aquinas’s thoughts within the last century, Paul Synave and Pierre Benoit “put forth the thesis that God can be the author (auctor) of Scripture even if not every individual “idea” contained therein is his.”[note]Paul Synave and Pierre Benoit, Prophecy and Inspiration: A Commentary on the Summa Theologica II-II, Questions 171-178 (New York: Desclee Co., 1961), 88.[/note] In this way, we can come to accept that some of the events recorded in Scripture may not be the “ideas” of God, but were perhaps permitted to further the faithful’s understanding of God, or to accurately record the history of God’s people in order for future generations to come to a more complete understanding “in the fullness of time.”

One’s understanding of God’s “authorship” of Scripture can be developed even a step further, in recognizing that the Church’s own tradition doesn’t necessarily claim or imply that God is the author of Scripture in today’s commonly-understood sense. Yes, the Church does teach that all Scripture is inspired. Even within the canon of Scripture, we learn that, “All Scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for refutation, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (2 Tim 3:16). However, as John Henry Newman writes,

“With this perspective, we can further see that it’s possible that God is the origination point of the ideas in the Bible without being seen in the modern sense as the “author” of every word of Scripture. It is thus easier to understand how some instances of evil and atrocities may have entered the inspired body of Scripture.”[note]John Henry Newman, On the Inspiration of Scripture, edited by J. Derek Holmes and Robert Murray (Washington, D.C.: Corpus Books, 1967), 10.[/note]

With a fuller understanding of how to deal with the development of Scripture and of apparent contradictions therein, our attention can now turn to some of the specific “dark passages” noted earlier, and others, reflecting the nature of good and evil presented in the Bible.

The Old Testament presents so much that could be perceived as evil being perpetrated, permitted, or encouraged by a God that we are to believe is all-good, which creates the contradiction modern skeptics are quick to point out. In the book of Genesis, God destroys everything on earth except for Noah’s immediate family and the animals with them in the ark. In the book of Exodus, “the Lord” killed all the first-born in the land of Egypt. Further, he buried Pharaoh’s army and chariots in the waters of the Red Sea. In the book of Exodus, one encounters several events that call into question the inerrancy of Scripture or the goodness of God. As the final of the ten plagues of Egypt, “the Lord struck down every firstborn in the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh sitting on his throne to the firstborn of the prisoner in the dungeon, as well as all the firstborn of the animals.” (Exod 12:29). Later, in the book of Ezekiel, recalling the Israelites’ exodus, the prophet records God saying that due to their rebellion and lack of following his ordinances, he said,

“I swore to them in the wilderness that I would disperse them among the nations and scatter them in other lands, because they did not carry out my ordinances, but rejected my statutes and desecrated my sabbaths, having eyes only for the idols of their ancestors. Therefore I gave them statutes that were not good, and ordinances through which they could not have life. I let them become defiled by their offerings, by having them make a fiery offering of every womb’s firstborn, in order to ruin them so they might know that I am the Lord.” (Ezek 20:23-26)

A modern scholar using a Method B historical-critical approach would look at each piece of text independently, seeking answers from the historical context as to what it meant that God struck down all the firstborn of Egypt, or that God purposefully gave the Israelites statutes that weren’t good, or caused them to offer their own children as sacrifice. Someone using Method A exegesis would look elsewhere in the Bible to find explanations for these passages, to back up their belief that God would not do such evil things. Before one tries to build a Method C approach to these Scriptures, it’s helpful to turn to one additional sequence of Old Testament events: the various ways that the Old Testament authors tried to understand the “hardening of the heart” of Pharaoh.

Pharaoh’s hardened heart – expressed through his reactions to Moses and the plagues that befell Egypt, and how he chose to continue to respond to those various events, provides interesting insight into the Old Testament authors’ own wrestling with God’s causality of such events, and even God’s causality of Pharaoh’s hardened heart. As Ramage calls out in Dark Passages, “Although the majority of the time Exodus narrates that ‘the Lord hardened Pharaoh’s heart’ (Ex 9:12) or even reports God’s words, ‘I will harden his heart,’… in other places it states that ‘Pharaoh hardened his [own] heart’ (Ex 8:32), or simply that ‘Pharaoh’s heart was hardened.’ (Ex 7:13)[note]Ramage, Dark Passages, 189.[/note] This is a fantastic way to illustrate to a Method B exegete, via the development within the text describing the sequence of events, how Aquinas’s concept of the substance being the same even though the writers’ understanding continued to develop, is at play as it relates to how much God’s own action or causality played into these events. It then becomes relatively easy to turn the conversation toward how Israel and its Old Testament writers continued to grow in their understanding of how active God was or wasn’t in causing some of these evil events. The point of the text is its sum, not the individual parts. If, as Ramage points out, “most Method B scholars concur that the Pentateuch as we have it today is the product of many different authors writing over many centuries,”[note]Ibid.[/note] then one could also point out that all the various authors and redactors who eventually brought us the text as we have it today could have removed the discrepancies if they thought that it was important. The fact that they did not illuminates that the text is intended to impart a different lesson – perhaps not a definitive teaching on God’s causing (or not causing) evil, but instead to teach some other truth about God, or God’s intent for his relationship with man.

One final challenging text in the Old Testament that is helpful to understand as a “dark passage” is the destruction that the book of Deuteronomy indicates the Israelites rendered in their conquest of the promised land, seemingly at God’s own command. As Israel went on to conquest the promised land, God ordered the killing of every man, woman, and child. As recalled in Deuteronomy,

“And the Lord our God gave him over to us; and we defeated him and his sons and all his people. And we captured all his cities at that time and utterly destroyed every city, men, women, and children; we love none remaining.” (Dt 2:33-34; cf. 3:6; Jo 6:21)

“But in the cities of these peoples that the Lord your God gives you for an inheritance, you shall save alive nothing that breathes, but you shall utterly destroy them, the Hittites and the Amorites, the Canaanites and the Per’izzites, the Hivites and the Jeb’usites, as the Lord your God has commanded.” (Dt 20:16-17)

These passages express a sentiment that also shined through in the earlier citation from Ezekiel 20, in which the author assumed that God willed the evils that befell the Israelites on their journey, as a response for their turning from his ways. Now, in Deuteronomy, there is an assumption that God’s active will of these events is the cause of them. Again, one sees the earlier assumptions of the Old Testament writers, not yet fully developed through the ongoing revelation of God to His people, perhaps misattributing the cause of some of these historical events. To help explain these, it is helpful to look at another area of development through the Old Testament, the development of the “accuser,” the earliest and developing form of Satan through Scripture. Some of Method B comes into play as one considers the development, over time, of the character of an “accuser” who initially stands pointing out the cause of evil events, into a character who openly antagonizes Biblical characters like Job, and then into a character who is in opposition to God. If Method A and Method B exegetes can agree upon the development of another key Old Testament “character” like the one who developed, in the fullness of revelation, into Satan, then a Method C synthesis can point back to the development of Old Testament authors’ understanding of the causality of evil events. Whereas in one period of Old Testament writings it may have been assumed that God willed or caused events like those in Deuteronomy relating the conquest of the promised land, as the divine pedagogy revealed more of God’s fullness to man over time, authors were subsequently able to hone their understanding of what God may have actively willed versus what God may have simply permitted, allowing room for man’s free will.

As time went on, as the divine pedagogy continued, the authors of Scripture came to understand more deeply that God may not have been the active cause of every evil that had previously been attributed to him. Yet, there was no reason to go back and emend earlier texts, since those same authors probably also understood (via a Method A traditional understanding) that the message being taught, or the substance being relayed, was not impacted by those incidental facts or points of attribution for evils that occurred. It is only in the light of Method B, looking at each bit of Scripture in isolation and alongside its historical context, that some of these questions start to arise, like how a supposedly-good God could allow or perpetrate such evils. As this paper has explored, there are still well-reasoned Method C responses that have developed, and will continue to develop, which respect Benedict XVI’s wishes that we “mutually enrich” the old and the new, in the case of scriptural exegesis marrying Method A with Method B into a new, more mature Method C understanding. This new understanding and these responses help to account for some of the problems and “dark passages” presented in the Old Testament. But more importantly, this understanding will continue to grow as mankind proceeds toward its ultimate end in God, because, as the prophet Isaiah wrote, “[God’s] thoughts are higher than [our] thoughts.” (Isa 55:9b)

Submitted October 3, 2017, for the course “Introduction to Scripture”, Instructor: Dr. Matthew Ramage.

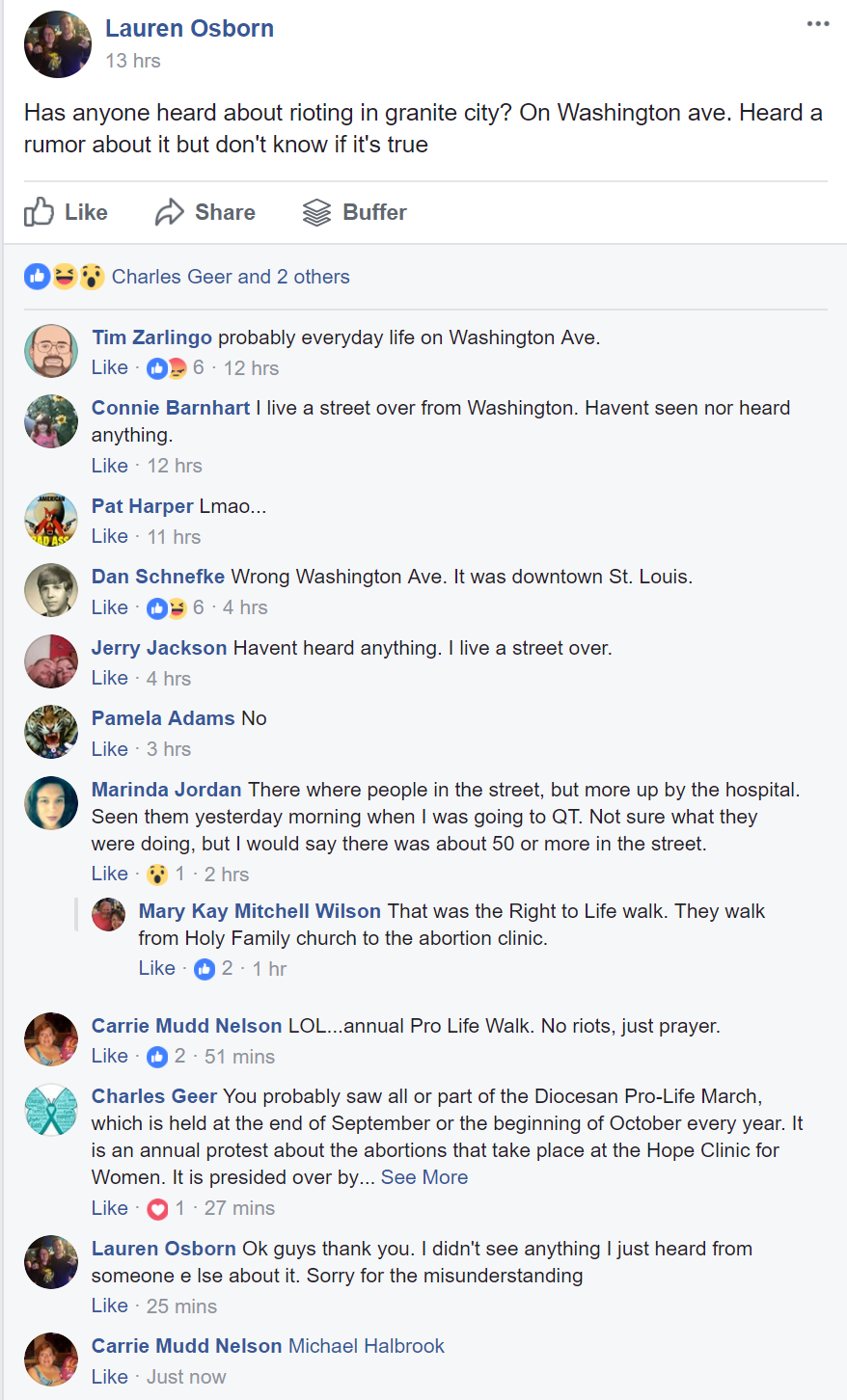

Image: Rembrandt van Rijn, Abraham’s Sacrifice. Etching and drypoint on paper, 1655.